A new paper just published in Cell Metabolism shows just how effective intermittent fasting is against obesity and metabolic derangement: Time-Restricted Feeding Is a Preventative and Therapeutic Intervention against Diverse Nutritional Challenges. The study was done on mice, but I don’t see any reason that these results shouldn’t be completely applicable to humans. Here’s the abstract:

Because current therapeutics for obesity are limited and only offer modest improvements, novel interventions are needed. Preventing obesity with time-restricted feeding (TRF; 8–9 hr food access in the active phase) is promising, yet its therapeutic applicability against preexisting obesity, diverse dietary conditions, and less stringent eating patterns is unknown. Here we tested TRF in mice under diverse nutritional challenges. We show that TRF attenuated metabolic diseases arising from a variety of obesogenic diets, and that benefits were proportional to the fasting duration. Furthermore, protective effects were maintained even when TRF was temporarily interrupted by ad libitum access to food during weekends, a regimen particularly relevant to human lifestyle. Finally, TRF stabilized and reversed the progression of metabolic diseases in mice with preexisting obesity and type II diabetes. We establish clinically relevant parameters of TRF for preventing and treating obesity and metabolic disorders, including type II diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and hypercholesterolemia.

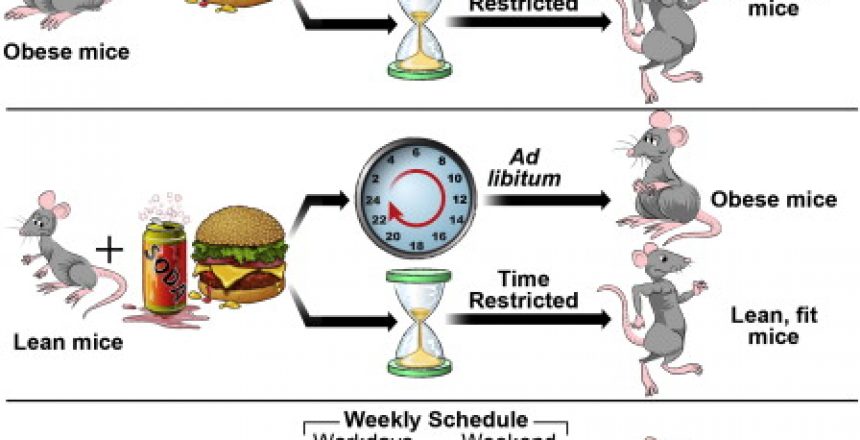

The study also supplied the graphical abstract you see at the top of the post, which highlights the study well.

The mice in each group were provided with the same type of food; the only thing that differed was the timing of the feeding. It was found that intermittent fasting (“time-restricted feeding”) protected against obesity, despite the fact that the same amount of calories was ingested; glucose tolerance was improved and insulin resistance reduced; and inflammation was reduced.

Mice fed an FS [fat + sucrose] diet ad libitum (FSA) consumed the same amount of calories as mice fed within a 9 hr window of the dark phase (FST), yet the FST mice gained less body weight over a 12-week period (21% compared to 42% for FSA mice).

It’s not clear to me whether the 21% gain in the IF mice was a “normal” weight gain or an abnormal gain of fat, but in any case they gained only half as much as the ad lib fed mice, and let me emphasize again, both groups consumed the same number of calories.

Of great interest is that the duration of intermittent fasting correlated negatively with weight gain; that is, the longer the fast, the less the gain. Even restricting feeding times just a bit retarded weight gain.

Longer daily HFD [high-fat diet] feeding times resulted in larger increases in body weight. For example, a 26% gain was seen for 9 hr TRF (9hFT), whereas a 43% gain was seen for 15 hr TRF (15hFT). Mice fed ad libitum (FA) gained 65% under these conditions.

There was even an advantage in weight gain (much less) when animals did time-restricted feeding on weekdays but ate ad lib on weekends.

What I take away from this study is not only the efficacy of intermittent fasting to fight obesity and metabolic disorders, but also that almost any restriction whatsoever of feeding times ought to be of benefit. For instance, I’ve made the point previously that until quite recently, most everybody fasted for 12 hours daily, that is, between dinner and breakfast. Seems to me that if everyone adhered to that schedule, it could make a huge dent in the obesity epidemic. And of course, longer fasting was even more beneficial.

Another aspect of this is that it demolished CICO, or calories in, calories out, as an explanation for obesity.

Another point I made recently in my podcast was that intermittent fasting is not that difficult, at least it isn’t for me. Sixteen hours seems a breeze; in effect, you’re only skipping one meal, breakfast, and you can still have a cup or two of coffee in the morning, which readily decreases appetite. In my experience, however, a diet lower in carbohydrates facilitates this, as you just don’t seem to feel the same type and urgency of hunger when you eat lower carb.

In sum, more evidence that intermittent fasting is a uniquely healthy practice and is also anti-aging. However, as with other aspects of dealing with obesity, it requires some effort – it’s not a pill you can pop. So to me it seems that only those who are already reasonably fit, i.e. those used to making some effort, will take advantage of it.

10 Comments

This is another great addition to the evidence of the efficacy of intermittent fasting for improving a wide variety of physiological health markers, but I’m weary when you state that a single study “demolished CICO, or calories in, calories out, as an explanation for obesity.”

It’s definitely remarkable that this study showed such significant reductions in fat accumulation simply by restricting feeding windows, calorie intake being unchanged, but the numerous ward based human metabolic studies showing that overall calorie intake is the main determinant in fat gain/loss cannot be denied.

Not to mention, one noteworthy result of the study I noticed was that the TRF mice were able to run much longer on the treadmill. Perhaps the TRF mice simply stored less fat because they were running around more and had more energy? Of course, if the metabolic healing properties of IF mean increased energy to move around more, that’s another big pro for IF.

I think IF is great. I’ve been doing leangains for 3+ years, but I learned through trial and error that simply restricting your feeding window doesn’t give you permission to eat willy nilly and still have guaranteed fat loss, even if you do still achieve the other various physiological benefits of IF. This is especially true for naturally endomorphic big eaters like me. At the end of the day my own successful fat loss really came about when I started counting calories and getting my macros on point. There’s a certain point when there’s no way around the truth that, some way or another, if people want to lose fat they will have to restrict their calories.

One of the greatest parts of IF, in fact, is that it can really help improve satiation with less calories. There are several mice studies showing that they will eat less overall calories when eating ad libitum with restricted feeding windows rather than around the clock, which obviously results in improved body composition.

My big long term goal is to one day find dietary “zen” when I can eat ad libitum, not count calories, and maintain my ideal body composition. IF will be an essential tool for me to achieve that, no doubt about it, especially considering the increasingly shown physiological benefits it will reap. I really think we’ll start to see what IF can do for humans in the next 10-20 years as the research evolves. It’s still quite young and most of the data there is exists in mice studies.

Pete, thanks for the comment. I agree that IF doesn’t give permission to eat just anything. As for CICO, yes, calories taken in minus calories expended is a necessary and sufficient condition for weight gain. The question is, why are more calories taken in? If for example high glycemic load foods are eaten that spike insulin, it causes fat storage and then the person must eat more to maintain energy levels. Thus more calories taken in. Wild animals, and plenty of humans, regulate their hunger well, so that calories in = calories out. The question is, why is hunger disregulated in some people, so that they eat more than they burn? IMO, probably because they eat high carb and have high insulin levels, the food is stored and doesn’t “register”, or at least not as much, as having been eaten.

As for why the mice on TRF did not gain as much weight, probably metabolism was increased by IF and they burned off the food eaten better than the ad lib fed animals.

“The question is, why is hunger disregulated in some people, so that they eat more than they burn?”

Aye, there’s the rub. I know I eat too much. The irony is I don’t even like food, I just put something in my belly so it will STFU and leave me alone. My neighbor can eat a laughably small amount, then go outside and pull the transmission out of his car. He isn’t trying to restrict calories; he just doesn’t want any more.

By following your suggestions, I doubt I will ever become thin, but I may become less fat. I am down 50 lbs so far (one lousy pound a week). It ain’t easy, and I could gain it all back in the blink of an eye, but I saw what happened to my mom, and it really is a matter of life and death.

Excuse me now while I autophagy.

Maybe a stupid question, but have you tried a very low carb, high fat diet?

Affirmative. Lost the 50 lbs on vegetables and hamburger patties. Still weigh 3 big ones, though. Long road ahead.

Stomach not amused by mandatory IF restrictions. Could be hard sell.

Intermittent fasting seems the way most animals eat in a natural environment. As humans (in most cases) food is too readily available and we do not have to actively grow our own food and hunt. Therefore, we do not go through long periods of fasting. In nature, how many animals do you see that are overweight/obese to the point that they are dragging ass? Not many, because they would fall easy prey. It seems intuitive that intermittent fasting is the natural approach to “dieting”. Same thing goes for cardio – it doesn’t seem natural to go on long steady bouts of running (unless you are a herd of animals migrating across the Great Plains of Africa). Short periods of sprints (to catch prey and avoid predators) seems to be the more “natural” way of cardio exercise. Intermittent fasting, intermittent sleep, and interval cardio seem the way to go.

Eric, you’re right on both counts. Many large carnivorous animals eat only once every few days; it’s the herbivorous that eat constantly, because they have to. And of course I agree on the running. Interesting thing about that is how I used to read running magazines and they all claimed that long distance running was somehow natural, that humans did it all the time in ancestral environments. I used to buy that argument too. Sprints on the one hand, walking on the other, with some moving things around (weights).