Exercise prevents cancer, an idea which is one of the main themes of my book Muscle Up. How much does it lower the risk? A recent meta-analysis found up to 42% less risk for 10 different cancers, including esophageal, liver, lung, kidney, and many other cancers. An interesting question is how exercise prevents cancer, and some recent research sheds light on this.

It’s often assumed that exercise prevents cancer because those who exercise are in better physical condition, and that seems at least partially correct. For instance, obesity is associated with cancer, and if exercise helps to prevent obesity, then it would prevent cancer too. But science shows that acute bouts of exercise can inhibit the growth of cancer cells.

Blood taken from men after exercise inhibits cancer

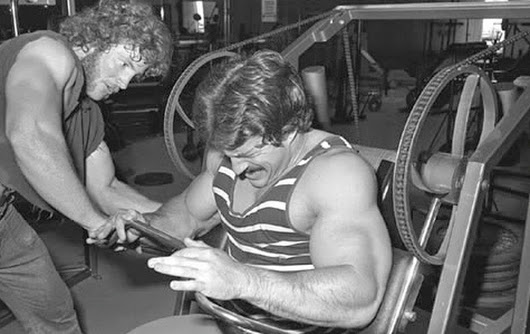

A remarkable study looked at how blood serum taken from men post-exercise dramatically inhibited the growth of cancer cells.

The experiment took 23 young men, average age 22, and had them do a bout of high-intensity cycling, 6 1-minute intervals at 90% max, with 1-minute rest intervals in-between. They had blood drawn before the bout, and then at 5 minutes, 1 hour, and 24 hours post exercise. The blood was centrifuged and the serum (liquid part) was placed into media that contained cancer cells, which were different types of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Controls were cells grown in their usual media, without human serum added. The cells were allowed to grow for 7 days, and then counted. Chart below shows the results.

Huge inhibition of cancer growth, up to 75% using serum taken 5 minutes post-exercise.

Why does this happen? One possibility is lack of growth factors. Insulin was not a factor, since they found no difference in insulin between pre- and post-exercise specimens, but IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) was different, so that may be the answer.

There’s also evidence that can let us speculate that weight lifting might be superior in this regard (as I’ve long maintained), because molecules secreted by exercising muscle, called myokines, may be involved in suppression of cancer growth.

Basically, every bout of intense exercise floods your bloodstream with anti-cancer molecules, and/or it removes pro-cancer molecules.

This isn’t the only study that has found such an effect.

Exercise serum inhibits prostate cancer cell growth. Researchers believe that the exercise serum increases expression of the p53 gene, which arrests cell growth.

Exercise abolishes cancer-promoting effect of fat tissue

Animals fed a high-fat diet – which we know usually consists of large amounts of seed oils and sugar – become obese, with large amounts of adipose (fat) tissue, and extracts of this tissue placed in a medium growing cancer cells increases the proliferation of those cancer cells.

Physical activity can completely abolish this effect of high-fat diets on cancer proliferation.

We hypothesized that voluntary physical activity (PA) would counteract the deleterious adipose-dependent growth microenvironment to which a breast cancer is exposed. We show that PA altered the adipokine secretion profile of adipose in a volume-dependent manner. This alteration resulted in growth inhibition of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells in culture. Furthermore, stabilizing adiponectin receptor 1 expression in the cancer cells made them resistant to the cell cycle entry effects that accompany obesity.

Fat tissue generates cytokines that promote the proliferation of cancer cells, and physical activity diminishes or abolishes the effect, which is dose-dependent, i.e. more exercise means less cancer promoting cytokines.

In another study, blood serum from breast cancer survivors was used in media to see its effect on cancer cell growth. Six months of exercise training in these women increased VO2max and muscle strength, and reduced cytokines. Yet serum from these exercise-trained women had no effect on cancer cell growth.

Serum taken after a 2-hour exercise session did reduce cancer cell viability.

Systemic changes to a 2 h exercise session reduced breast cancer viability, while adaptations to 6 months of training had no impact. Our data question the prevailing dogma that training-dependent baseline reductions in risk factors mediate the protective effect of exercise on breast cancer. Instead, we propose that the cancer protection is driven by accumulative effects of repeated acute exercise responses.

So cancer prevention is not (entirely) a matter of your level of physical fitness, but a matter of how intensely and often you exercise.

In animals (mice) that were implanted with tumor cells, voluntary running reduced tumor growth by over 60%. The researchers believe that exercise mobilized natural killer (NK) cells, which attack cancer.

Together, these results link exercise, epinephrine, and IL-6 to NK cell mobilization and redistribution, and ultimately to control of tumor growth.

This result suggests that exercise might actually attack cancer cells in people who already have cancer.

For anti-cancer therapy, exercise

Every time you do a bout of high-intensity exercise, you flood your bloodstream with anti-cancer molecules, or remove molecules that promote cancer growth.

One substance that’s been overlooked by researchers doing these experiments is iron, and cancer feeds on iron. Exercise that is intense enough and protracted enough can cause iron deficiency. If someone exercises intensely and regularly, he would likely be depriving any incipient cancer cells of the iron they need to grow.

There’s a widespread belief that cancer just happens, and that, except for not smoking, there’s not a lot you can do about it. Nothing could be further from the truth; there are many ways to prevent cancer.

You can add exercise to the list of cancer prevention interventions.

7 Comments

Some dozen articles back I posted this:

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/106/7/dju206/1010488/Sedentary-behavior-increases-the-risk-of-certain

https://blogs.ergotron.com/files/2011/11/MakeTimeBreakTime_x500.jpg

Now, what are practical guidelines from that?

If possible in one’s circumstances, should one set a timer for 60 minutes through the day and do 50 burpees hourly?

Or should one exercise as hard as one can once per day or per week?

No question about the effectivity of exercise, but we all have restrictions in daily life in terms of time and location – so what should we do in practice to optimize anti-cancer effect?

My links above suggest doing sth. little once per hour or so is more important than doing something herculic once per day.

Also, given this data, I wonder if people with decade-long jobs of sedentary nature vs. physical nature (say, postman, delivery man, …) would have significant differences in cancer rates.

Another note:

Together with hormesis (by chemicals, radiation, exercise…) this seems to me to point to the idea that our self-repair systems are not really active generally, but need to be kind of kick-started regularly, else they tend to be mostly inactive.

Evolutionary this would make sense: Our ancestors should have been always be forced to be physically very active to succeed in evolution – exercise is nothing special, it was all the time in the past the very norm in some form or another – our modern sedentary life is evolutionary novel (among other novelties only just affecting our or the very few last generations) and becomes a problem just because of that – it seems to deregulate and hinder mechanisms that were ubiquitous before (just like we are evolutionary completely unprepared for the sudden overload with refined sugar or vegetable oils as primary food source).

P.S.

Concerning vegetable oils – I noticed that here in Germany the dominant kind in most foodstuffs is rapeseed oil – which looks, from an omega-3/6-perspective, less unhealthy than the oils that dominate the US food market; what is your opinion about that specific vegetable oil?

Your links do suggest not being sedentary, but the results in my article above only show the effects of intense exercise. Whether you’d get the same results by getting up from the couch and doing a set of burpees would need to be determined I think, although it certainly seems a lot better than being sedentary.

As for your question on rapeseed (canola) oil, it does have a better omega-6/3 ratio than other seed oils, but it shortens the lifespan of hypertensive rats, even in comparison to soybean oil. “Although the feeding experiments were performed under very simple and restricted conditions, these results suggest that the rapeseed oil prepared for human use contains a factor (s) which is toxic to SHR-SP rats.” It’s also an industrial product. Avoid.

Thank you.

I was ignorant that “canola” is indeed rapeseed oil, I did not know the correct translation and mistook it for sth. different.

(OT)

I just came about this article

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ratio_of_fatty_acids_in_different_foods

If you eye “Oils” you’ll find beef tallow – grain vs. grass fed – the values for the omega-6/3- ratios

are very different from those of your article:

https://pdmangan.com/is-grass-fed-beef-worth-the-money/

The source the Wikipedia article is citing gives different results than those from the source in your article.

If I am not mistaken that should be examined, lest grass-fed beef would indeed be superior over grain-fed.

Going to the source of that data, the results are indeed different, although based on one measurement. As the article states, “Whatever the ratios, beef tallow is not a rich source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, with only 3.45 percent in grain-fed and 1.9 percent of the total in grass-fed.” So even if their analysis is accurate, the main point of my article stands, that whether you eat grain-fed or grass-fed beef doesn’t matter, as they have a trivial effect on total polyunsaturated intake, especially if you also use seed oils or eat nuts, chicken, or fish. All of these foods swamp the difference between grain and grass fed beef.

Also, the difference in values they got could be due to the grass-fed beef coming directly from a farm. It’s my understanding that even most grass-fed beef is grain-finished, and possibly this one was not.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DKHrxvkWkAEtTqr.jpg

thank you for a very useful article. Can exercise help prevent all types of cancer or only certain types?