Exercise is a uniquely beneficial health practice, one that improves health, decreases mortality, and that just generally improves overall quality of life. Anyone who exercises regularly knows the feeling of well-being that exercise causes, both during it and afterwards. But there are obviously both different kinds of exercise, and different levels of intensity. To improve physical fitness, the goal of exercise, one must pay attention to the importance of exercise intensity.

What exercise does

The effects of exercise are many. Exercise

- improves insulin sensitivity

- increases cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max)

- increases strength of bones and muscle

- decreases risk of cardiovascular disease

- decreases cancer risk

- improves mental health

- prevents frailty and decline in aging

- helps weight control.

All of these effects are intertwined and can’t be readily separated.

The effects of exercise can be viewed according to the FITT principle: frequency, intensity, time (duration), and type.

For frequency, intensity, and duration, in general, the more the better, but it’s possible to overdo it. Why is that? Because exercise means the placing of stress on the body with the aim of improving health, and is therefore a form of hormesis, in which a low dose of a stressor or toxin results in better health and stress resistance. As such, exercise is characterized by the J-curve typical of hormesis; see chart below. (Source.)

A low to moderate amount of exercise improves health compared to being sedentary, while a very high amount (such as hard daily training at elite level athletics, or ultramarathon running, for example) can lead to overtraining and worse health. In this article, we’ll be concerned with how much exercise is necessary rather than with excessive exercise and overtraining.

Since exercise is by definition a stress, any physical activity that does not place a stress on the body doesn’t improve fitness. While any physical activity itself can improve health and is far better than being sedentary, aerobic (cardiorespiratory) fitness is a much stronger determinant of health. See chart below – aerobic capacity is twice as strong a reducer of cardiovascular risk as is physical activity.

Therefore, to lower your health risks, just moving around isn’t enough. The activity you do must be intense enough, or long enough, or frequent enough, or some combination of these, to increase fitness. Type of exercise is also important, since some forms of exercise are inherently more demanding than others. Boxing, for example, places a greater demand on the body than zumba.

Levels of exercise

Intensity of exercise appears partially to override the factors of frequency and duration. For example, higher intensity exercise improves aerobic fitness more than lower intensity, even when duration is adjusted so the the same number of calories are burned.

High-intensity interval training improves cardiorespiratory fitness as much or more than traditional steady-state aerobic exercise, in far less time.

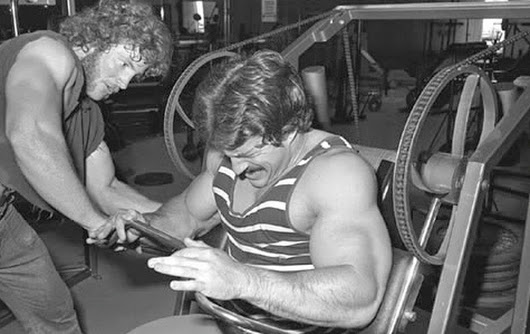

In bodybuilding, other things equal, intensity trumps volume and frequency.

Low intensity exercise improves fitness only in people with a low level of fitness. This is an important point.

Walking, for example, improves insulin sensitivity in obese, type 2 diabetics. These people have a low fitness level and high insulin resistance, and walking therefore represents enough of a stress on their bodies to improve their health.

Now, suppose you’re a regular reader of this site, you lift weights and/or do other forms of high-intensity training, you are of normal weight and have good insulin sensitivity. Will walking improve your health further?

Not likely. You need either more frequent exercise of the same intensity you’re already doing, a longer duration of it, or an even higher intensity.

Fitness level determines whether an exercise improves it

If you have low aerobic fitness, almost any exercise will help. Someone who’s been ill and in bed for a long time will improve just by getting out of bed. Likewise, walking can improve the fitness of someone who’s overweight and sedentary.

But how can we determine whether a given bout of exercise improves our fitness or not? In other words, how can we put this matter on a more scientific basis?

Exercise physiologists have done this, and have determined that exercise intensities below 45% of VO2 reserve in subjects with high fitness do not increase fitness, while for those with low fitness, at least 30% of VO2 reserve is necessary.

So, what’s VO2 reserve? It’s the difference between resting oxygen consumption (VO2) and maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max). VO2 reserve differs greatly between fit and less fit individuals.

In the real world, without the assistance of an exercise physiologist, probably the best way to look at exercise intensity is through metabolic equivalents, or METs.

One MET is the amount of energy expended at rest. Different types and intensities of exercise can be expressed in multiples of METs.

The above chart shows some sample exercises in terms of METs. A more comprehensive list can be found here.

High-intensity vs steady-state exercise

Steady-state exercise (“aerobics” or “cardio”) has long been prescribed as the exercise that uniquely increases cardiorespiratory fitness, but we now know that high-intensity exercise does that as well, and in less time.

One problem with steady-state exercise, such as jogging or treadmill running, is that the only way to increase the exercise stress is by increasing the duration of exercise. You see this method of training in distance runners, for example, who end up running for hours daily to increase the amount of training they do.

In contrast, using high-intensity training, you are always working out at the edge of your physiological capabilities.

So, with high-intensity training, there’s never a question whether you’re exercising intensely enough to increase your fitness, because you are always doing so.

Conclusion

Low-intensity exercise improves fitness only for those who are not fit. As you move up the fitness ladder, exercise needs to become more intense to improve fitness.

28 Comments

Good article. I’m always reminded of the UK 8 year study of different exercises and their impact on longevity. All exercise was better than none, but racquet sports were the clear winner in reducing mortality from all causes ( 47% reduction compared to 28% swimming and aerobics). Tennis is of course a high intensity interval sport ( at least singles tennis is), and the exercise durations are usually rather short. They didn’t look at weight lifting but the aerobics group included gymnastics. Cyclists and runners showed the least benefit but that is probably, as P.D. points out, a function of acclimating to it over time. HIIT is probably best.

Thanks, Paul. According to the list of METs for sports I linked in the article, racket sports (and handball) rank highly indeed, right up there with boxing.

It would be really interesting if weight lifting had been considered, I wonder if the important factor is the intensity rather than the resistance aspect.

Their is certainly some restistance in raquet sports, but a lot more in swimming and cycling, nether of which rated highly, I wonder how water polo would rate? It also involves raquet sports’ high degree of both short tem intensity and the precise had eye coordination

Also, I wonder how short the duration of the intensity can be?

Why not have short (say ten seconds) of intensity, but do it every hour of your time awake, most (say 80 % days of your life ?

A ten second flat out sprint (even on the spot) is SO exhilarating. Likewise 8 flat out burpees. Not to mention being probably a lot more evolutionarally sound than hitting the gym a few times a week.

Sidetrack…when we talk about burpees, we mean “just” the basic sort, without either a pushup at the bottom or a jump (or pull-up) at the top, right? Just down -> feet out -> feet in -> up, right? I’ve been doing sets of pull-up burpees at the end of my upper-body sessions the last few weeks.

For my money the jump at the end is a really important element of the health benefits of burpees.

Jumps far more than the other variation you mentioned – the pullup.

My body, and particularly the brain seems to feel the ‘ jolt ‘ of a jump as almost peculiarly satisfying.

Then I read about the quite extraordinary benefits both dementia and parkinsons disease sufferers experience from regular jumping – particularly when they’re ‘aiming’ for some specific landing target. For example to avoid obstacles such as low slung ropes etc. Then it didn’t seem such a weird idea.

in fact there’s so much of the ballistic going on in burpees. And you can do them anywhere. Even people whov’ve never done a burpee in their lives will be bouncing through at least a few in days of regular bodily reminders.

Jumping to avoid becoming prey or in battle (later in human evolution) seems to me one of the gems of who we are.

Cheers, Stuart. I’ve been fighting a kneecap tendon strain for a while now, called “jumper’s knee”, among other things, so jumping burpees are a bit iffy for me right now. That said, I did 4 30-sec sets at the end of my upper body session just now, without managing to make it worse.

I think I agree, the pullups are nothing compared to jumping. And I aggravate my long-term slight shoulder strain when I do pushups, so it’s just the pushup-less jumping burpees for me for now. And that’s enough.

In other news, I got Mrs & me a sphygmomanometer last week. I’m not worried about our BPs, as my new doctor insists I’m in “great shape”, and my perceptions of variation in BP are to be expected with the kind of training I do. And he measured me at 110/70 and 120/80 on different days (as well as 140/90).

The pharmacist who sold me it

( https://tinyurl.com/Blutdruckmessgeraet –hours of fun!)

gave me a demo first, and was quite impressed with my pulse being 53, considering I’d not sat there and calmed down first or anything. “Are you training for iron man?”

For those keeping score at home, 144 / 80 pulse 72 just now, whilst sitting with doggie on the couch 45 minutes after the gym.

I think that part of the concept of HIIT is that you get your H.R. up to close to 100% max but then you only recover to about 70-80% and do it again. But your idea Stuart of 10 seconds an hour all day is rather clever and has probably not been studied. You would frequently but briefly be at max HR, but then fully recover. I’m going to try it and see how I feel .

One hitch I see here is that one would need to do more than 10 seconds to hit max HR. In HIIT, you might not hit max HR until the 2nd or 3rd repetition. For example, I do a 20-sec sprint cycle at the end of my weight workout, and I’m sure I hit max HR, but if I did it at the beginning, I would probably need more than one bout of cycling.

It would be interesting to check a habitual raquet baller’s H.R. I doubt whether they EVER hit max. Even ‘long’ rallies just don’t last long enough.

Aren’t we talking about different things anyway? I’ve no doubt HIIT gets you fitter faster.

But will it maximize your lifespan?

Depends what is more important to you of course.

I’d even stick my neck out and say that exercise as an excuse to consume more calories is a bit like a cat chasing its tail. Just digesting food wears you out doesn’t it? Not suggesting starvation

of course,

The more I do it, regular (many times/d , 7d/w) really short intense exercise – in other words studiously avoiding even approaching max H.R – just seems to make more longevity sense

No studies to back this up whatsoever I don’t think they’ve even been done yet.

There was a study where researchers performed before and after skin and muscle biopsies on subjects who then did cycling intervals about 2 days a week only if I recall correctly, but the amazing thing was that the histology of the tissues converted from “old” to “young” after just several months. In fact the histology was identical to a 20 year old’s. This doesn’t prove, but may suggest a longevity effect from HIIT.

Paul, I’d love to see that paper.

Watched it on a video about 6 months ago, maybe you tube, I’ll try to search it out.

Perhaps it was this one:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28273480

That said, I think this study is partially wrong in that it is unlikely that otherwise untrained seniors could achieve HIIT intensities on a typical weightlifting program for beginners, however an experienced lifter doing squats, deadlifts or cleans for sets of ten likely could…

Thanks – I wrote about that study and why they found less improvement with resistance training, here.

The research is discussed on the mercola.com site dated May 27,2017. The video, which is fascinating, is also there . It actually shows the microscopic histologic changes induced by HIIT for only 6 mins/week. I’m going to try to re-watch it in between patients.

OK, thanks, Paul.

Hi Stuart – you may be right about racquetball. As for exercise and longevity, animal experiments show (so far anyway) that it does not extend maximum lifespan, only average lifespan, so in a sense it’s not truly anti-aging. It does extend healthspan of course, and humans who exercise live longer, although there’s an issue of genetic confounding. Athletes live longer, but are more likely to have gone into athletics because they have a genetic aptitude for it.

It’s very easy to get to HR max if you play squash with a better player, believe me 😉

I am an average-poor player. Novices can’t last 30 minutes against me without pauses to recover. One had to stop at 15 min, he was dying… and he is a frequent runner.

While I don’t disagree with anything here and my training is slanted toward high (but rarely 100%) intensity, I have found that infrequently (not more often than every 3-4 weeks) doing much longer low-intensity sessions, like a 2-4 hour bike ride, seem to be quite beneficial as well.

Also, while spinning may be close to sprint-running from an energy expenditure perspective, I am a big believer that there is no other exercise that comes close to running sprints for maintaining overall youthful physical abilities. There is something about sprints that activate a large amount of the nervous and muscular system simultaneously in a very natural way. To me they are one of the best, if not the best indicator of true physical age since there are plenty of people who can jog or do a cycle sprint who are still physically old, but only a truly young person can do an all-out sprint.

I’m with you all the way Drifter. Being a able to sprint is the ultimate indicator of age.

I think the neuromuscular stuff Drifter mentioned is itself an antiaging factor. So flat out sprinting may well be a lot more powerful than a mere metric.

Old age is not itself necessarily an impediment to flat out sprinting any way.

Slower times of course…

Hi Drifter – I don’t disagree with that, but sprinting is also conducive to injury – something I know firsthand. A typical older person who sprints is likely to injure himself.

Yes, I have just spent six months recovering from a hamstring injury, so I can relate. That said and at the risk of presenting a circular argument, I learned a lot from it, as I have from many of my injuries. I will be much more diligent about hamstring conditioning in the future because of it and I’m now familiar with some interesting injury recovery compounds that I previously would have ignored. I play basketball so being able to do at least court-length sprints is essential for me. I think the bigger lesson is that young healthy people should never let themselves get out of sprint shape.

Now you guys have me wondering if the ideal might be run sprints on Monday, swim sprints on Weds., weights on Friday, and then a long slow hike over the weekend.

I’m a bit confused about intensity re: weightlifting. Let’s say two guys overhead press to complete screaming I-am-all-that-is-man failure, but one did 20 reps and the other heavier weight for 8 reps. Both reached failure, and both were extremely intense in different ways- is there a metric by which we could determine who was more “intense”?

IMO, both are equally intense. Another way of looking at it is if one of them were substantially stronger than the other; both lift to failure, so both have reached the maximum intensity their muscles can bear. Also, just to add, several studies have reported no difference in hypertrophy between lifting heavier vs lighter weights, so long as done to failure.

Awesome, exactly what I wanted to hear (I’m the 20-rep-to-failure guy, wanted to confirm I’m not a wuss). Thanks P.D.

Nicest Post Thank You My Admin. https://www.freepornde.com