A recent study found that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) robustly increased both aerobic capacity and mitochondrial function in both old and young people.

The older people saw a greater increase in mitochondrial function, because they had a lower baseline function. This study has been making the rounds, calling HIIT “the best anti-aging exercise”. Here we’ll see how to turn lifting weights into a maximum anti-aging workout.

Decline in mitochondrial function is strongly linked to age and aging. In young people (and other young organisms), mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, function perfectly and with high efficiency, but with aging comes a falling off of that function. As mitochondria generate power, the decline literally means a decline in overall energy, the energy you feel. It probably explains a lot about why children have seemingly limitless energy, and why exercise improves the amount of energy you actually feel in everyday life.

Increasing mitochondrial function in older people improves their physiology and makes them much more like a young person.

HIIT vs resistance training

One little hitch for us weightlifters:

Here we report that 12 weeks of high-intensity aerobic interval (HIIT), resistance (RT), and combined exercise training enhanced insulin sensitivity and lean mass, but only HIIT and combined training improved aerobic capacity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration.

The researchers reported no effect of resistance training (weightlifting) on better aerobic capacity and mitochondrial function.

Similarly, HIIT, but not continuous aerobic training, led to increases in PGC-1α, the molecule that upregulates mitochondrial biogenesis, i.e. signals cells to make more mitochondria to enhance energy generation.

Does all this mean that strength training does not improve health, or that we must perform HIIT to improve mitochondrial function and reverse aging?

Not at all.

We know that strength training increases VO2max, the measure of aerobic capacity. While VO2max is a general measure of function, including heart rate, circulation, hemoglobin, and lung function, it also includes mitochondrial function, the ability of the cells to use oxygen to make energy. For a good review, see Resistance Training to Momentary Muscular Failure Improves Cardiovascular Fitness in Humans: A Review of Acute Physiological Responses and Chronic Physiological Adaptations.

So, why didn’t the people who did resistance training in the new study see any improvement in mitochondrial function and aerobic capacity?

Most likely because of the way they trained.

I can speak from experience that most people who train with weights are hardly even trying. How so? They

- do the traditional 3 sets of 10 reps, and rest between each set

- they don’t lift until failure, but stop at a given number of reps

- their between-set breaks are far too long

- they spend a good deal of their gym time socializing or looking at their phones

- they do isolation, not compound, exercises

This isn’t meant to be boasting on my part, just simple observation; in contrast, I

- perform one set of each exercise to failure

- move quickly to the next set

- do compound lifts

- rarely socialize and don’t even own a phone, much less take it to the gym

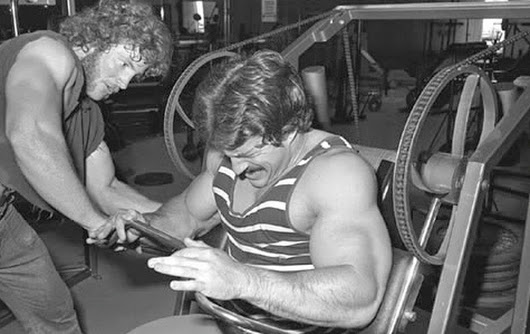

I frequently have to stop after a set to catch my breath, and this is especially obvious when I do big compound exercises, such as squats, deadlifts, T-bar rows, weighted dips, and the like. But I can’t even say when I’ve ever seen another weightlifter in my gym stop to catch his breath. I don’t know, maybe I’m not looking hard enough, but it’s striking.

When the new study put their trainees in resistance training, it’s highly unlikely that they did a high-intensity routine. They most likely did a standard 3 set per exercise protocol, with plenty of rest between sets, 3 days a week, etc.

Most people aren’t psychologically cut out to do high-intensity weightlifting. It’s too demanding. Which explains the general lack of progress seen in most gym-goers.

If your heart and lungs are not working intensely, at least some of the anti-aging benefits of strength training are lost to you.

How to increase mitochondrial function and VO2max with weightlifting

1. Here’s a good example of high-intensity strength training: Shawn Baker, M.D., deadlifting 405 pounds for 20 reps. Note that toward the end he pauses, and it looks to me like he does this not so much for his muscles, but to catch his breath.

Trying to do this x 4 years- now on #zerocarb 405lb DL x 20 reps

50 years old-NO drugs, hormones, supplements, carbs or belt

Objectivity!! pic.twitter.com/84aoKjoCq7

— Shawn Baker MD (@SBakerMD) March 23, 2017

Dr. Baker is 50-years-old, eats zero carb, and is a world-record holder in his age group for 1000 meter rowing.

Compound exercises, like deadlifts, squats, dips, bench, overhead, maximize the use of heart, lungs, and circulation, and will robustly increase mitochondrial function. Isolation exercises like biceps curls and triceps pulldowns are much less effective for this.

Note, this is not Crossfit, which carries a high risk of injury. All exercises must be done with good form and attention to safety.

2. Move quickly to the next set. “Quickly” is subjective of course, but don’t wait minutes or until you feel all rested and ready. Attack your workout.

3. Do an adequate number of repetitions. Lifting at your max weight for low reps (1RM) does little to improve cardiovascular conditioning.

4. Finally, you can always add a set or two of actual HIIT at the end of your strength training. For example, a 20-second all-out bout on the stationary cycle at the end of my workout leaves me gasping for breath. Sometimes I do a set or two of jump rope.

Conclusion

Weightlifting robustly increases VO2max and mitochondrial function, but it must be done right. Since the extent to which strength training improves VO2max depends on initial state of conditioning, someone who is already highly trained but wants to improve VO2max even more should add some HIIT to his strength training.

23 Comments

I find 3 sets of 5 or more in the power clean to also be particularly helpful, as well as ending my workout with a brief stationary bike set that works my heart rate up to about 160 or 170 for at least a minute, or some sprints to end the workout.

I tried some power cleans recently, I agree that they get you going. Kicked my ass.

I joined a “strength and conditioning” class. Three days a week. For 45 mins they do two compound lifts (bench, dead, squat, front squat, military press) at least 5 set each, then they do 15 mins of “as many reps as possible” which has a lot of different exercises (varies each time: could be goblet squats, kettle swings, lunges, box jumps, pushups, situps, pullups). I find that the last part always kicks my ass and leaves me gasping. Whether or not it is doing great things for my mitochondria, I’m pretty happy with the visible results on my body!

That deadlift, lower body strength, is where it’s at, wish I knew that earlier in this thing called life, but hay it’s never to late for any of US.

How do you handle your progression? Do you just play it by ear when you’re in the gym, or do you have some sort of system?

Pretty much play it by ear. I mainly try for more reps each time rather than increasing the weight, always go to failure, and pick a weight that will let do 8-12 reps.

His uses a razor and slices it so thin it liquefies in the pan with a little oil. No wait, that’s his system for doing garlic.

The link you give to the study keeps giving me a “Privacy Error” warning. I would really like to access the original paper to see what exactly the resistance training protocol consisted of. Like you I suspect it was far less intense than the HIIT.

Probably Adel Moussa over at Suppversity will get around to analyzing it soon and we’ll see how it stands up to his scrutiny.

I’ve been working on HI weight lifting since last summer. But I’m “still stuck” in the routine of doing two sets, as I never really seem to believe I’ve gone hard enough to failure in one set. The second sets are normally shorter though, as one might expect.

I’ve had people tell me not to work so hard, not to punish myself so, to cut back on the weight to avoid the obvious “pain” I’m suffering during my sets (I already go lighter than I would if I were doing conventional lifting); most recently a trainer/worker at the gym INTERRUPTED me during a set, as he wanted to pull back a plate on the machine I was using. Had to tell him to wait til I was done, then explained what I was doing. The point is, I obviously seem to be working hard as it worries my fellow gym members.

Topic drift…sorry…

I’ve recently adapted to fasted workouts, but just to clarify, we *do* still want to feed up on BCAAs and protein ASA training’s over, right? I mean, if I end my session at 18 hours into a fast, I shouldn’t continue fasting another couple of hours to maximise fasting, rather, I should feed myself right away, right? My goal is to correct the muscle deficit I’ve been suffering under my entire adult life, fat-burning is secondary to that.

Ditto for short HIIT sessions — whey shake immediately afterwards?

Nick, yes, that’s correct. If you do a fasted workout, don’t continue fasting after, have whey or a meal.

PS: lol at your gym peeps thinking you’re working too hard.

Thanks for the quick reply. Just that I’ve been reading (internet) that you won’t burn muscle when exercising fasted as some would have you believe. But ideal for building muscle & recovery is to feed properly afterwards. Glad I’ve got that right.

I’ve learned so much since I stumbled across this site over a year ago!

Hi Dennis,

I’ve been an avid reader of your site for over a year now, thanks for everything you do. Coming up on my fifth blood donation soon because of your advice.

My question- something I’ve never able to square away is the fact that Blue Zone cultures never exercise in the traditional sense vs the HIIT/strength training advice backed by science I read here. I don’t doubt for a moment that the claims of improving mitochondrial function etc. are true, yet it seems that the people with the longest, healthiest lives engage in extremely low-intensity movement all day long as opposed to an high intensity short duration workout. Why the disconnect between science and what we see in real life?

Thanks for your time

Hi Matt. I’d say it’s a question of what’s optimal. Certainly, long-lived Blue Zone people are active, but as I’ve written, they’re also religious, family oriented, are short and small, eat low calories (relatively), have low iron, may have good genetics, and so on. In aging, it’s become clear that mitochondrial function is important, and we know this from both human and animal studies. We know that athletes live longer than non-athletes, although it’s not clear that exercise is the sole cause. So, being athletic and improving VO2max and mitochondria is the best shot at living a long time, IMO.

PD I just found and read this report on research on “Hot water bathing” Apparently it help with blood pressure, and may contribute to reducing chronic inflammation, which is often present with long-term diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and reduces the risks of heart attacks and strokes. Not quite as good as HIIT but definitely far better than nothing. I wonder if you have any comment on this ?

https://theconversation.com/a-hot-bath-has-benefits-similar-to-exercise-74600

Hi Bill, I think that’s legit. I came across the research on saunas a while back and it seems convincing, so hot bathing should have benefit too.

Hi P.D.

And thanks for your Blog.

May I ask you what do you think of HMB (Hydroxymethyl butyrate) to avoid muscle catabolism?

Thanks a lot.

Hi Marco, I think HMB has some merit, but it may be matched by the much cheaper leucine, of which HMB is a derivative.

“Shawn Baker, M.D., deadlifting 405 pounds for 20 reps”

He’s not even using a mixed grip – so that is POWERFUL grip strength!

Great article, good to know! One question I have is how to incorporate Nautilus/Heavy Duty/Body By Sience training into this scenario? I currently do an almost entirely Nautilus program of 9 exercises that stimulates all of the major muscle groups with direct/variable/balanced resistance. However, to do this, only one of the exercises is a compound exercise – the Nautilus Duo Squat. Is it possible to get the benefits of Nautilus equipment AND this mitochondrial/metabolic adaptation at the same time?

I’m thinking that more of your exercise than you think may be compound exercises. For instance, if you do overhead press, rows, lat pulldowns, chest press, all are compound exercises. In terms of cardiovascular conditioning, I find that nothing cranks up the heart and lungs like barbell squats and deadlifts. So I think if done right, you can get a decent CV workout on Nautilus only, but you might consider adding at least those 2 barbell exercises.

“… don’t even own a phone”

Did I ever tell you you’re my hero?

Ha ha, Matt, thanks! I still don’t own one!