Gaining muscle is easy – at first

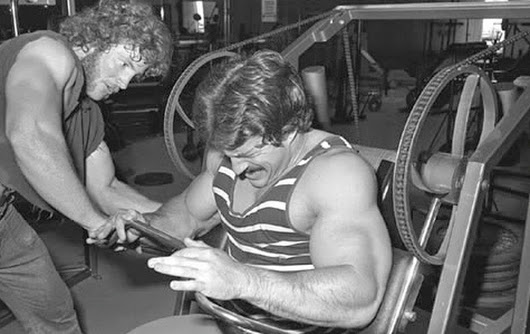

Beginners to weightlifting can easily pack on lots of muscle in their first year or two of training. For example, I gained about 30 lbs (13.6 kg) in my first year of training – all I had to do was train hard and eat plenty of the right food and boom, there it was.

After the first year or two, it becomes much more difficult to add muscle, mainly because you’ve approached your genetic limit. If it were easy, you could expect to see plenty of bodybuilders at your local gym looking like Ronnie Coleman, who at contest weight weighed 300 pounds (136 kg) at 2% body fat. Obviously, we don’t see many guys like that.

The problem is compounded by not wanting to gain fat. I’m a little paranoid about that, though possibly no more paranoid than lots of lifters.

The reason not wanting fat gains compounds the problem is that you may not eat enough to fuel muscle gains. Obviously you need to eat right to gain muscle, including enough calories and protein, but unless your training and diet regimens are finely tuned, you risk fat gain.

Bulking (overeating) may work for some people, but it’s a good way to gain fat. If you can’t diet the excess fat away, you’re stuck with it. Not to mention that it’s not a healthy lifestyle plan: insulin resistance goes up for instance.

How to get around the problem of gaining muscle without gaining fat? The solution is a simple one, which I call targeted lean mass gains.

Targeted lean mass gains

This system allows you to gain weight but in a targeted manner. Here it is:

- Weigh yourself daily. Anyone concerned about body composition should be doing this already. Daily weighing is an effective means of weight control, despite what they say in the mainstream.

- Instead of holding yourself to a set weight, one that you feel suits you, add one pound (0.45 kg) a month to your set weight.

- Train and eat as usual.

That’s it. This system allows weight gain, but in a gradual fashion, thus avoiding fat gain.

I’ll use myself as an example.

Six months or so ago I decided to shed some fat. I weighed 170 pounds, but I felt like too much of this was fat.

Through dedicated intermittent fasting, I lost up to 9 pounds (depending on the day I weighed myself) over the course of about a month. Virtually all of the weight I lost was fat, as I continued my regular training and kept my protein intake at over 1.2 grams per kg of body weight daily. My lifts continued as usual; in other words, I continued with the same weights and reps for each lift, so I know my strength didn’t decline, and I therefore lost no muscle.

It’s been shown that regular strength training combined with adequate protein intake can result in simultaneous fat loss and muscle gain.

I weighed 163 pounds this morning. My target weight for February would then be 164 pounds, for March, 165, etc.

In this way, one can continue to eat just a bit more in order to fuel muscle gains. Gaining one pound of muscle a month, or 12 pounds a year, would represent good muscle gains for an intermediate strength trainer, which I consider myself to be.

But by holding oneself to a one pound gain per month, one will be much less likely to add fat.

You could make your target higher, say 2 pounds a month, but that amounts to 24 pounds a year. If you can add 24 pounds a year of muscle, you don’t need a system like this, you just work out and eat.

As mentioned above, daily weighing is effective for weight control in the context of weight loss. Weight control in the other direction, weight gain, ought to be just as effective.

If a client came to me for guidance on either fat loss or muscle gain, I would have him or her step on the scale daily. The idea in the mainstream seems to be that if you weigh yourself daily, you won’t be able to handle any disappointment when you don’t meet your target loss (or gain), and you then abandon your weight loss (or gain) program.

Frankly, the idea that you’ll be so disappointed that you stop your program is an idea worthy of children. By encouraging people to think this way, people trying to lose (or gain) weight are primed for stopping their weight loss or gain program at the first sign of resistance.

6 Comments

I am doing something similar but I also note that Volek and Phinney write ones body weight can vary as much as four pounds a day.

Isn’t there a maximum amount of muscle anyone wants to carry? At a point the thighs start rubbing together, the same with the upper arms and chest, talcum powder is necessary to prevent chaffing. What then?

Sure, but I suppose that depends on both individual taste and genetics. I think most men don’t need to worry about it because they’re not able to put on that much. For the rest, back off on lifting if you want less muscle.

I have determined that I would need approximately 130 grams of protein daily after a resistance work out in order to facilitate muscle hypertrophy (I am 170 lbs currently and I would guess that my body fat index is in the low teens if not fairly close to single digits). Is this a correct calculation on necessary protein intake? I have wondered about it since a couple of weeks ago when I realized how difficult it was to accomplish that “feat.” Even when I’m ravenous (particularly in the days following a heavy resistance work out) I have noticed that it seems like a ridiculous amount of food. Is that the point? I understand the place that whey has and I also utilize it but getting those extra 40 or 50 grams in, while doable, seems so unnecessary. Then again, I have also plateaued in the last year in my gains and perhaps not eating enough food is the culprit. What do you think about my visceral aversion to the massive protein intake? Thanx in advance.

If you use the figure of 1.6 g/kg, then you’d be needing about 120 grams, and that’s if you’re putting on muscle like gangbusters. If you’re an experienced lifter, and it sounds like you are, then you don’t need that much. You could get by with 95, according to my calculations. See my post on “optimal protein intake”.

Thanks for sharing your experience! I too have positive experience with IF – I found it effective and easy to incorporate into my schedule.